By Margaret MacDonald of ABALOBI

What do you get when you put three organisations on a tropical island in the Western Indian Ocean with eight tablets, five smartphones and one mobile monitoring app? And just for effect – let’s add three octopus and a bucket of juvenile fish? Any guesses?

Well it may not roll off the tongue, but the answer is a fruitful collaboration which enables the development and trialling of a mobile monitoring app used to facilitate community-based co-management and sustainable use of marine resources. How close did you get?

In March 2020*, members of ABALOBI, an organisation that works with small-scale fishers to co-design mobile app platforms to facilitate monitoring and livelihood opportunities, and the Blue Ventures team travelled to the island of Anjouan in Comoros to test and refine a mobile monitoring app, the Monitor App.

ABALOBI and Blue Ventures are working with Dahari, a Comorian NGO working with local communities on rural development, biodiversity conservation, and terrestrial and marine resource management approaches.

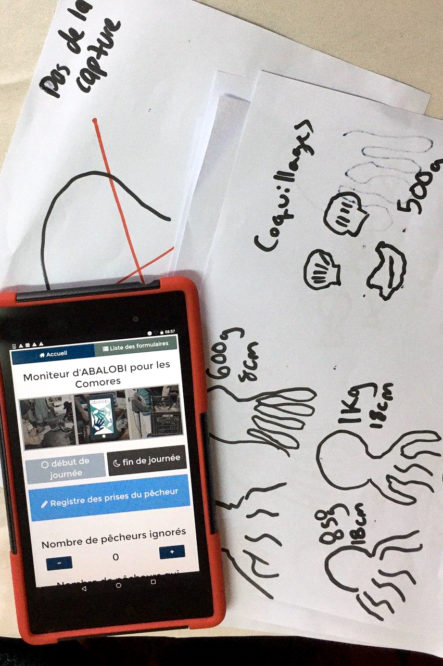

The Monitor app is a tool that will support community-based monitoring and enable fishing communities to use the data to manage their resources sustainablyWorking closely with the Dahari marine team, the Monitor app is a tool that will support community-based monitoring and enable fishing communities to use the data to manage their resources sustainably. Testing of the Monitor app in Comoros enabled the teams from ABALOBI and Blue Ventures to trial the new app with Dahari, who have been conducting catch monitoring with local communities in collaboration with Blue Ventures since 2016. The app was tested at the Dzindri ya Ntsini, one of the catch landing sites where Dahari has been conducting catch monitoring and developing the capacity of local fisher associations representing four communities to manage their marine resources.

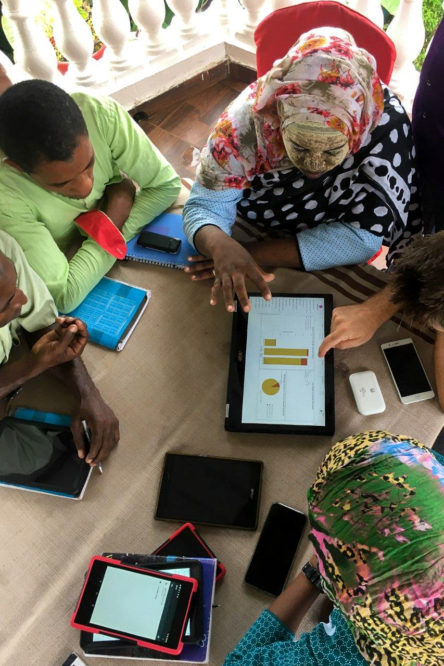

All three teams had been working together to design and develop a monitoring app that would make data capture easier for fishing communities in Comoros. However, the most important part of the co-design process happens in-field with the community monitors and data technicians themselves. For this reason, the trip to Anjouan Island was a critical part of the journey – this is after all a piece of technology that should assist communities in achieving their goals and objectives, as such their contributions and input are an key part of the development process.” noted Chris Kastern from ABALOBI.

After several months of development and background work, ABALOBI and Blue Ventures were ecstatic to finally sit with Dahari and a group of community monitors – the individuals who collect catch data – to test the app. Before heading to the fishing sites, the team walked Dahari staff members through the tech and practised logging catches. Co-design is a founding principle of this project. This means getting input and feedback from the team on the ground to ensure the product is right for the user – in this case, the community monitors and the organisation.

While we were itching to get to work with the fishing communities, our time at the Dahari office and in the main town of Mutsamudu was welcomed; it allowed the travelling ABALOBI and Blue Ventures teams to acclimatise to Anjouan. From sudden cooling downpours to spectacular sunsets, a never-ending supply of fried breadfruit with spicy local chilli sauce and colourful taxis that run around the clock, we were able to peek into the Anjouan way of life and spend time getting to know our new colleagues at Dahari.

The teams set out to test the Monitor app in the community of Dzindri ya Ntsini, a two hour drive from the Dahari office in Matsumudu. Before we started testing the app with the communities, we had the opportunity to join a data feedback session led by Dahari with three local fisher associations. This proved extremely valuable, as we were able to see how fishers understand and utilise their catch monitoring data to guide their management efforts.

Understanding the context is critical when developing a fisheries monitoring platform. It’s not enough to know what species of fish there are; it is critical to understand how fishers engage with their resources, how they fish and how they perceive the monitoring approach.

Finally, armed with smartphones, ABALOBI, Blue Ventures and Dahari headed down to the beach to put their efforts to the test. As the tide receded, the fishers, mainly women, descended onto the shoreline with a bucket and mwiri (a wooden stick used for catching octopus) in hand to glean the reef.

In one swift movement, one of the women captured an octopus on the end of her mwiri and turned to show off her impressive catchA number of the women called upon the newer faces from ABALOBI and Blue Ventures to join them. Despite our lack of knowledge of the local language and our particularly poor footing on the reef flat, a few of us joined the women fishers. We tentatively followed behind, grappling with the uneven surface, whilst the fishers effortlessly stepped across the flat, collecting juvenile fish and searching for octopus hidden in the crevices. In one swift movement, one of the women captured an octopus on the end of her mwiri and turned to show off her impressive catch.

Octopus fishers on the reef flat in Dzindri ya Ntsini | Photo Hannah Gilchrist

While the women caught fish, shellfish and octopus and we enthusiastically joined in (with much less skill!), the community monitors practiced using the app and posed methodology questions to their Blue Ventures and Dahari colleagues. They asked how the collection of shells should be recorded, and how octopus samples are most accurately recorded. Once there was agreement on the data capture method and the monitors felt confident in their ability to use the app, they ambled down the shoreline to await the fishers returning with the tide.

Three community monitors tested the Monitor app while their monitoring partner used the existing Open Data Kit Forms to ensure data was captured, as well as to compare the two tools. In general, the feedback we received was positive – the new app was easy to use and convenient as it allowed community technicians to simultaneously log their daily monitoring activity along with recording monitored catches and harvest.

“Chris, Chris! I logged 21 catches!”, yelled Amina, one of the community monitors, as she returned from the reef flat. Her enthusiasm and excitement was a good sign – our efforts to design an app that worked in the community context had clearly paid off.

As with any collective project, the journey was long and complicated at times, but our shared desire to deliver something that responded to the needs of the fishing communities kept the momentum up. A commitment to collaboration has been at the heart of the project from the very beginning; we believe as a collective team, that our founding principle of co-design is what has enabled us to create a product which we hope will empower these communities and others around the world to sustainably manage their marine resources, long into the future.

ABALOBI, Blue Ventures, Dahari staff and members of the community fishing associations in Dzindri ya Ntsini | Photo: ABALOBI

Margaret MacDonald works with ABALOBI as the Community Development Manager. Margaret and her colleagues work with small-scale fishers through the use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) and capacity building to foster more sustainable fisheries management and the realisation of thriving coastal communities. Margaret and her colleague Chris Kastern, traveled to Comoros to test the Monitor App in collaboration with Blue Ventures as part of a project funded by Oak Foundation.

Watch ABALOBI’s documentary ‘Coding for Crayfish’

Learn more about Blue Ventures’ catch monitoring work in Comoros

*the trip took place prior to COVID-19 quarantine and social distancing rules were announced in the respective countries